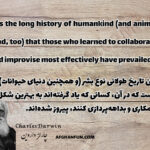

Zhvandun Magazine: A Window to Afghanistan’s Cultural Evolution

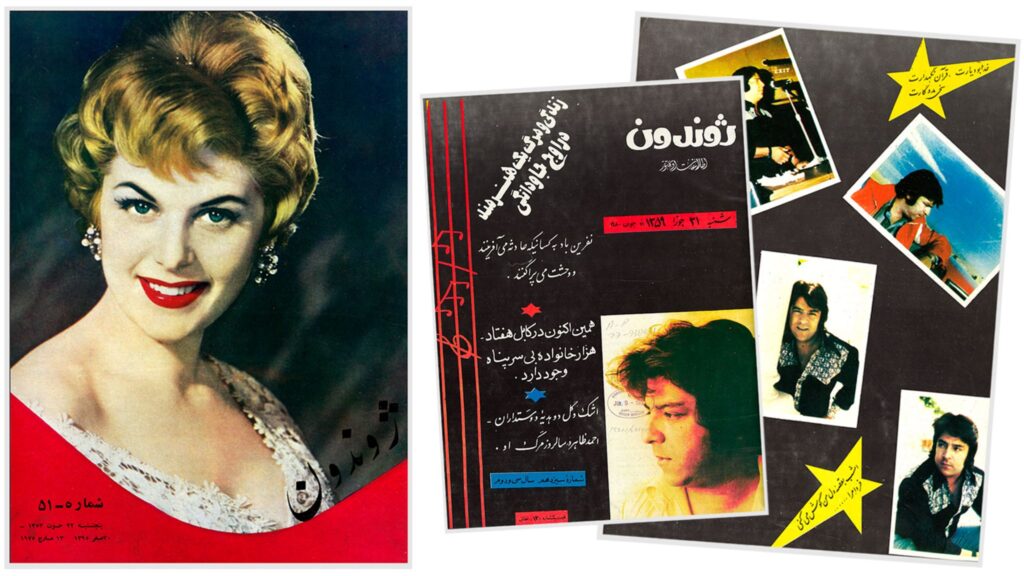

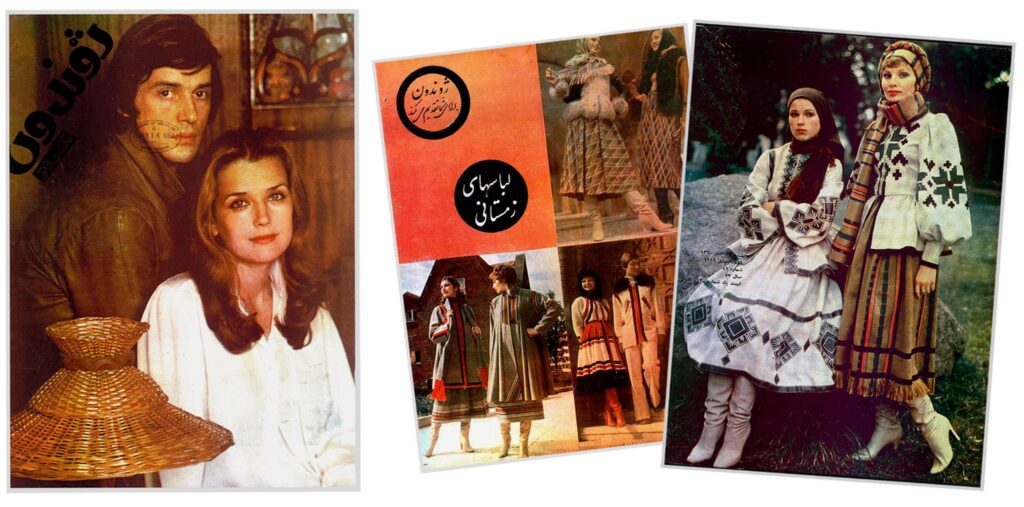

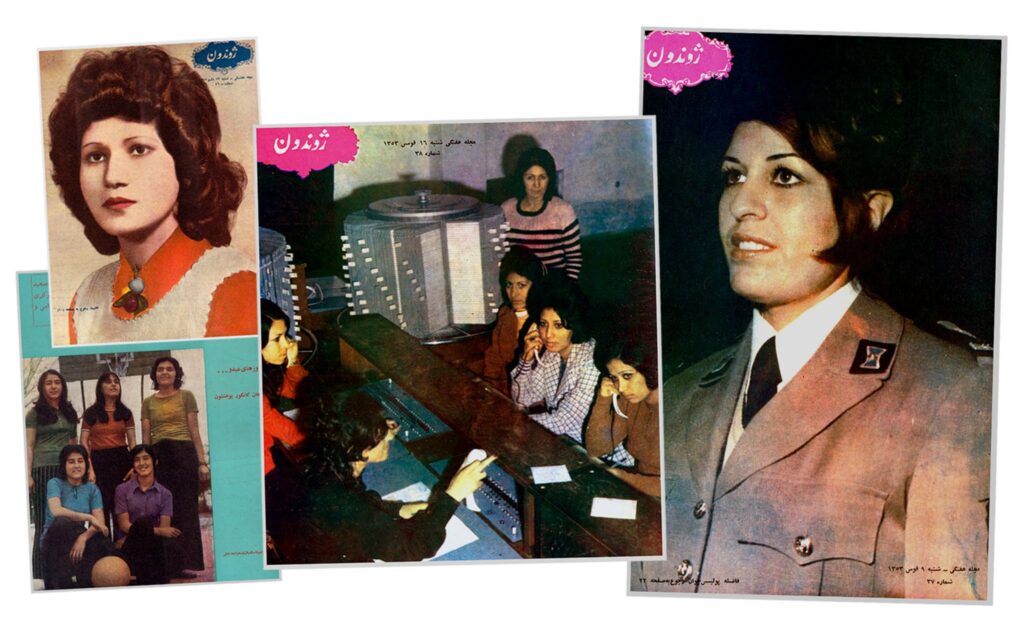

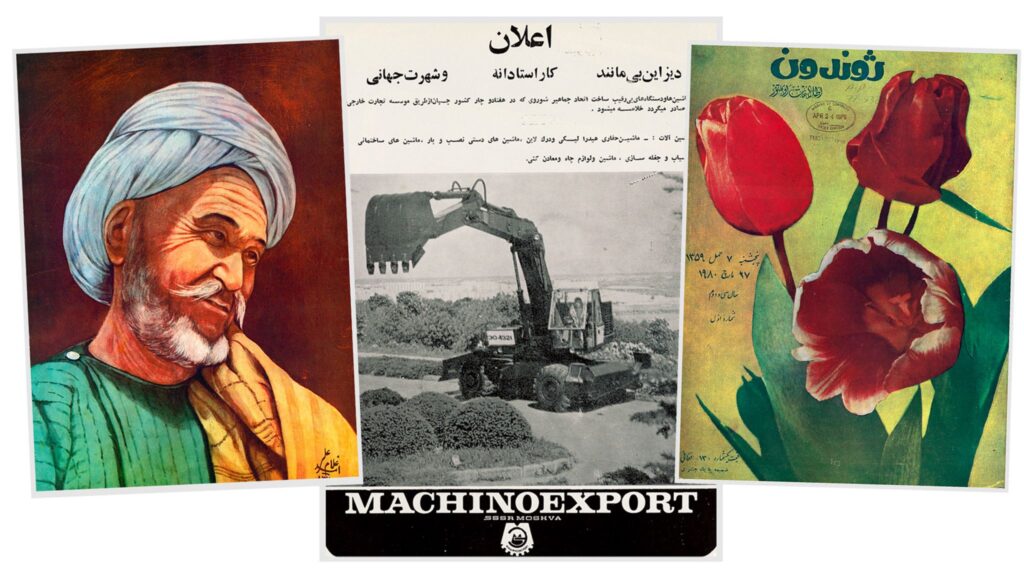

Bright, busy and colourful, newly digitised pages of Zhvandun magazine – Life, in English – reveal the aspirations of Afghanistan’s elite during decades of political and social change.

It rolled off presses through most of the second half of the 20th Century, mixing articles on global affairs, society and history with fun stuff on film stars and fashion.

Think, perhaps, of Time magazine with added poetry and short stories.

Over five politically tumultuous decades the pages of Zhvandun mirrored the upheavals of the time. But they also captured something more fragile – the ideals and dreams of their readers.

A Reflection of Society Through Advertisements

Zhvandun was produced for the few in a country where the great majority were illiterate.

Its authors and readership lived mainly in Kabul. They were progressive people, with time and resources to think about which film to see at the cinema or how to alter a hemline.

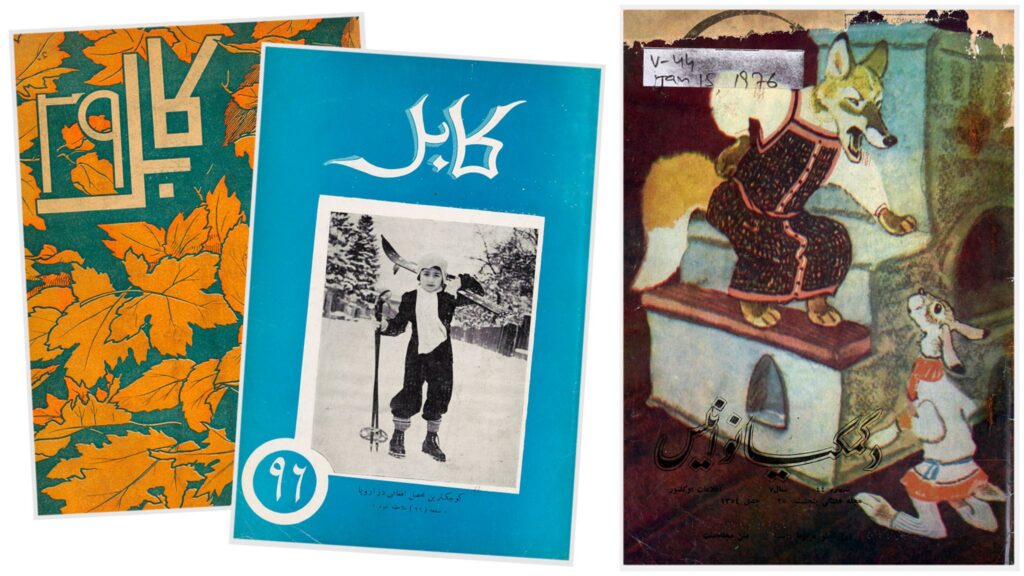

Zhvandun was on the more frivolous side of a host of magazines produced in Afghanistan from the late 1920s onwards.

Kabul magazine was the vehicle of the most celebrated Afghan writers and thinkers.

Adab (Culture) was the periodical of Kabul University, while Children’s Companion (Kamkayano Anis) was full of puzzles and stories.

Zhvandun arrived in 1949, a momentous year in the region. The old European empires were crumbling in the wake of World War Two.

Afghanistan’s neighbours, India, Pakistan and Iran, were crucibles of new post-colonial thinking.

Afghanistan had a modern state to build and at least some money in the bank.

King Zahir invited many foreign advisers to help him evolve his vision and sought support from both the United States and the Soviet Union.

The coming of Ariana Airlines in 1955 connected Afghanistan to destinations across half the world.

Its most famous route was from Kabul to Frankfurt by way of Tehran, Damascus, Beirut and Ankara. It was called the Marco Polo route, after the 13th Century Italian traveller.

Internally, Afghan cities that were separated by mountains and deserts became linked by regular flights.

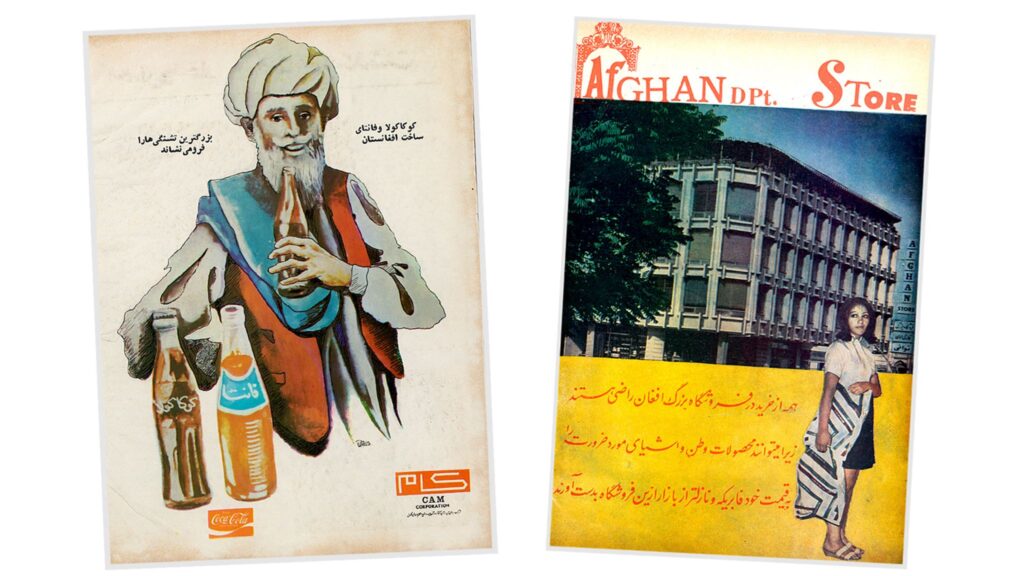

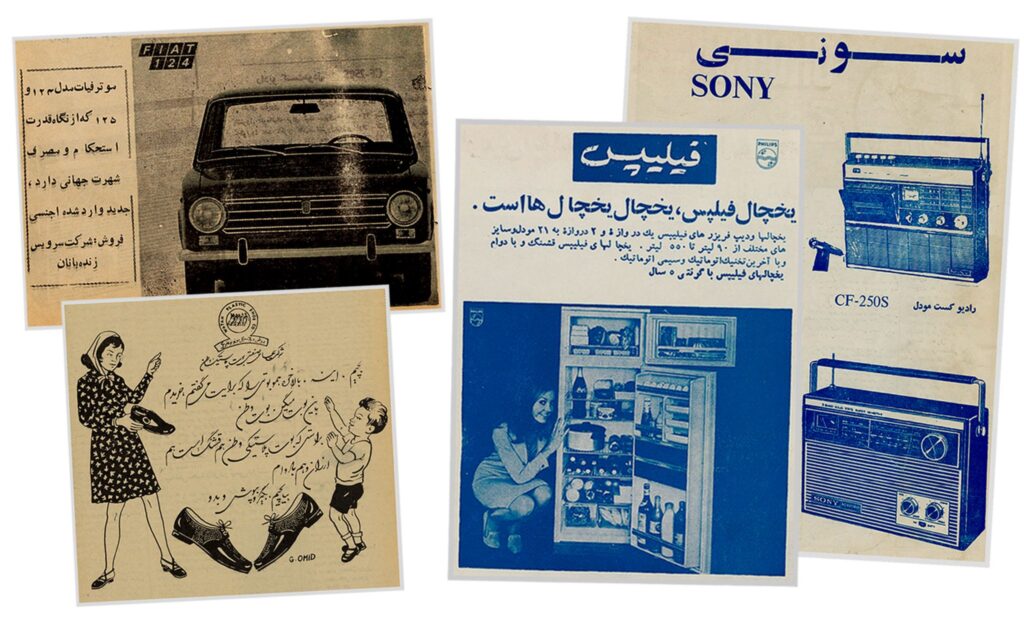

Advertisements creep into Zhvandun in the 1960s.

Cars, fridges, baby milk – such items would have been wildly beyond the reach of many, but for a few they represented the allure of lifestyle revolution, especially for women.

King Zahir’s cousin Mohammed Daoud Khan deposed him in 1973.

Casting aside centuries of tradition, he declared himself not king but president of a new republic.

It’s interesting to see the rise of local advertisements in Zhvandun during this period as Daoud Khan encouraged Afghan factories and services.

But Afghanistan seethed with new political ideas and rivalries and Daoud Khan was swept away himself by a group of communist army officers in 1978.

Known in Afghanistan as the Saur Revolution, this revolt heralded the generation of war that reverberates to this day.

Commercial advertisements disappeared with the Soviet invasion of 1979.

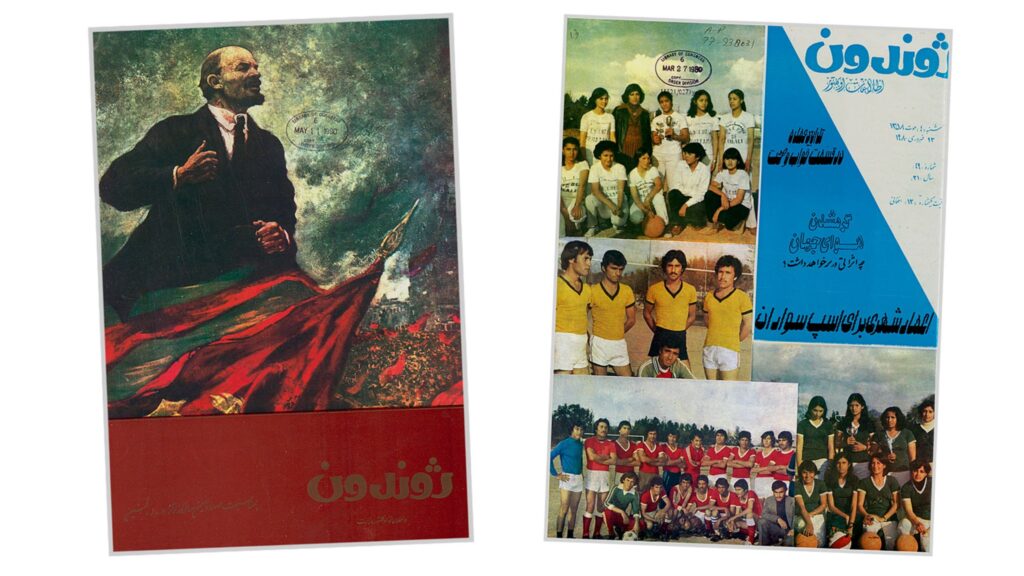

But Zhvandun continued to mirror dreams of a different sort.

Soviet film stars replaced Hollywood. Farm machinery appeared instead of tape recorders and fridges.

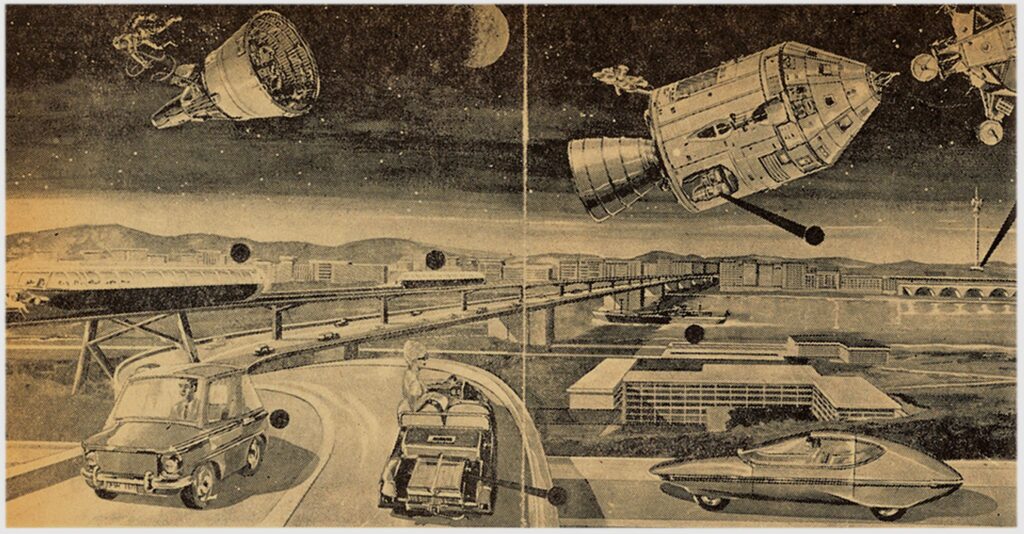

We find reflections even of the Soviet preoccupation with utopias.

From Hollywood to Soviet Stars: The Changing Faces in Zhvandun

Yet, for all the depictions of Lenin and gymnastics teams, there is something similar about the United States and the Soviet Union in their visions of modernity as revealed in Zhvandun.

The End of an Era – The Closure of Zhvandun

Zhvandun, Kabul and the other magazine titles all ceased publication after the Soviet defeat in the 1990s.

Those were chaotic times and many writers, printers and readers fled the country.

The rise of the Taliban meant that many never returned and this valuable social record disappeared.

But the Afghan journals were not the sort a reader might casually throw away. Collectors and libraries kept them carefully.

The US Library of Congress stored a near complete set across the border in Pakistan.

Hundreds of these magazines have now been digitised in partnership with the Carnegie Corporation of New York, as part of the World Digital Library.

They can be explored here – or read about the Afghanistan Project.

It’s hard to find the paper copies now, but they still turn up in street markets from time to time.

All images reproduced courtesy of the Library of Congress (World Digital Library) and the philanthropic foundation Carnegie Corporation of New York.

This entire page is copied from the BBC World Service

By Monica Whitlock

BBC World Service

February 2018